Why Jujutsu should be your next VCS*

November 19th, 2024 jujutsu git vcs

*Or… should it?

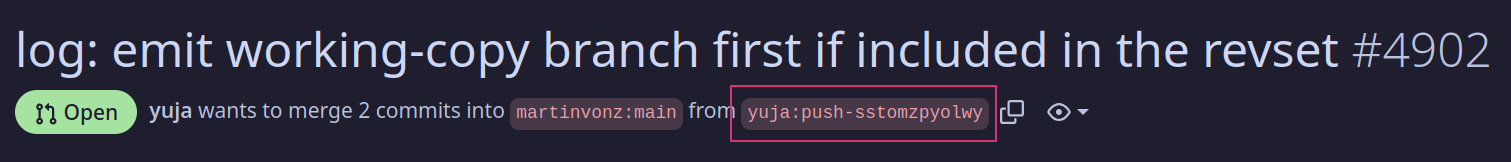

Like many people, my first exposure to Jujutsu was when I came across a PR someone opened on GitHub, with a very strange-looking branch name:

push-sstomzpyolwy? Seriously, who would name their branches like that? It

seems almost as if somebody let their cat walk on the keyboard for precisely 12

characters and then left it at that. Surely it couldn’t’ve been done by hand.

And surely enough, it was not — instead, people told me that there’s a cool,

new, exciting, Git-compatible VCS coming around called Jujutsu, or jj for

short. And it piqued my interest: there were some Git-compatible VCSes that came

before Jujutsu like Sapling, but in my

mind they never became mainstream enough for me to know about them — speaking as

a layperson who just accepts that everyone uses Git nowadays and doesn’t give

much brain capacity to think about how the status quo could be improved.

So, what’s so different about Jujutsu, and why are so many people praising it, even replacing Git with it as their primary VCS?

Instead of regurgitating what the creators have to say about Jujutsu, I’ll first attempt to gather my understanding of what Jujutsu is, and what it means for me personally.

My perspective as a newcomer to Jujutsu (as of the time of writing, I’ve been actively using Jujutsu for two weeks), and how I think the accolades it has garnered are very much justified, but the advantages it brings may not be relevant for everyone.

To put it very simplistically (which is going to be a running theme in this post), Jujutsu is like if Git had gotten rid of 80% of the concepts, commands and features that make it so needlessly complicated to understand, and in return offering a streamlined tool that can flexibly modify any point in time of your repository, reliably and intuitively.

In order to see why, we have to see what’s wrong with Git first:

Prelude. Unravelling the Flawed Predecessor

Now, I understand that many people (including myself) use Git just fine on a day-to-day basis to get code submitted, reviewed and fixed, and many may not even be aware of just how complicated it is.

To illustrate my point, let’s consider the very simple task of trying to get rid of some changes you have made to your code. Any seasoned Git user would immediately notice how vague that sentence sounded: it’s because in Git, depending on how far along the edit/commit/push process your changes have reached, the command to achieve that task is drastically different.

- If you made new files that haven’t been tracked yet, you could simply delete them and Git will treat them as if they have never existed.

- If the files you’ve changed are tracked but haven’t been staged, you can

run

git checkoutin order to remove the change — “Hey, isn’t that the command to switch branches and stuff?”, you may ask. To which I would respond with: “Exactly. Isn’t that kinda weird?” - If your changes are staged, then you first have to unstage it with

git restore --staged, and thengit checkout. Why? Because when you stage a file, Git will treat it as if it is holy and inviolable, meaning you have to first deprive it of its holy status, and then it may be removed as a mortal, otherwise Git will unleash its religious zealotry upon you. - If you changes have been committed, you now have many options:

- Reverting the changes with

git revert, which could create a dedicated commit just to fix your (assumed) stupid mistake. Way overkill. - Resetting to the previous commit with

git reset, with multiple options ranging from a pacifist approach of just removing the commit and leaving files unharmed with--soft, or the nuclear option of--hardand leaving no traces of your work behind. Kinda bad if you still want them back later, but you did agree to a permanent action after all :D - Using

git commit --amendto apply some hot glue and bandages on your commit - Using

git rebase -ito drop or amend your commit - And so on.

- Reverting the changes with

- Worst yet is that if you have already pushed your commit, you can now either

append a new commit to fix your previous commit, or you can

choose to be evil and useJust kidding;git push --force--forceisn’t as horrible as it sounds, and as long as you are following good, modern contributing guidelines (aka never pushing commits directly to your main branch), it is perfectly fine to use. You could always use--force-with-leaseto be on the safe side.

Wait, where were we? I think we’ve gotten sidetracked and talked way too much about Git in an article supposedly about something that replaces Git. Oh yeah. All of that is just for removing some changes. Here is a handy chart I found on the internet that explains only some of the operations you could achieve with Git via a smattering of discreet and discrete commands (Image credit: Tarun Yadav):

Yikes.

How does Jujutsu perform the task I just painfully described earlier with nearly an entire screenful of text?

You just run jj abandon. One command to rule them all.

Chapter I. Offloading the Cognitive Overload

The reason why Jujutsu is able to replace a handful of disparate Git commands with just one is mainly because it got rid of many conceptualizations that Git has, that might have been necessary in 2005 for performance or efficiency reasons, but are completely unnecessary with hardware of 2024.

For example, Jujutsu does not distinguish between untracked and tracked files,

because Jujutsu does not have the concept of “tracked” files — you don’t

opt into version control: instead you opt out of it, as all files that are not

excluded by your .gitignore are tracked.

Likewise, there’s no such thing as “staged” changes — all your changes are ready

to be made into a commit, without prearming them with git add. (We’ll touch on

how to select only some changes to be committed soon.)

jj abandon also works with existing commits: you just have to specify

-r <commit-id> to specify which commit you want to abandon, and it will be

abandoned. (Technically, it’s not the commit ID, but we’ll discuss it later.)

…Why does it work with both existing and soon-to-be commits, you may ask?

Simple. Because you’re always working on a commit. When you run

jj status, you may get a message like so:

M flake.lock

M hm-modules/hm-plus/programs/1password.nix

M roles/base/default.nix

M users/leah/default.nix

M users/leah/programs/default.nix

A users/leah/programs/jj/default.nix

Working copy : m[lxuqznxkqpl] 78[75d723a5b7] (no description set)

Parent commit: u[vxnmqmttrpn] 279[67cce5625] main main@origin | something

All of your changes are directly tracked by the “working copy” commit, and so nearly every action you can perform on your current version of the repository applies to commits as well.

This dramatic simplification of concepts and ideas is partly why Jujutsu is so appealing and intuitive: instead of the multiphased mind torture that is working with commits and changes in Git, in Jujutsu, everything works exactly the same way, since everything is a commit. (Some people also call it a revision. Or rev. It doesn’t matter.)

This same philosophy extends to branches and tags — Jujutsu blends them together into one concept, known as a “bookmark.” Unlike Git, where offshoots of the main branch must also be named branches, Jujutsu models them more akin to a tree of commits, where each commit has an ancestor and may have multiple descendants, and they do not have to be specially tracked or declared in any way.

Bookmarks are, in turn, a more flexible form of branches as they can be set to track an upstream bookmark (like how Git branches can track upstream branches), and automatically moved as you make changes to a “branch”.

Unlike branches, they can be moved around with the jj bookmark move command,

meaning that in the case where you have to move the branch HEAD somewhere else,

you don’t have to mess around rebasing in order to make it work. You can also

just leave them as-is and let them behave like static tags.

At this point you might say: “All this sounds cool and good, but how does it actually affect your workflow?”

Well, I am about to embark on a tirade about the most frustrating parts of Git that I encountered in the specific use case of Nixpkgs. If you’re allergic to that kind of thing, too bad — here goes:

Chapter II. Combating the Mindnumbing Tedium

Nixpkgs has a commit policy that I would really describe as Draconian in its pursuit for commit hygiene and separating changes based on what areas they change. For example, if a new contributor adds a package, its corresponding NixOS module and a unit test to ensure that the module is working, someone out there will make sure that you make exactly four commits, in this order, in this format of commit message:

maintainers: add foobarquux: init at 0.6.9nixos/quux: init modulenixos/tests: add test for quux

Rather understandably, newcomers often have issues fully adapting to this strict

commit standard, and will attempt to fix them by pushing more commits onto the

stack — but that is precisely what you shouldn’t do, since you should always

make sure your commit history has and only has these four items. And then, in

order to conform, they have to squash their additional changes on top of the

existing changes, usually via interactive rebase (git rebase -i), and then

fixing them one-by-one, sometimes requiring conflict resolution and manually

unstaging and restaging changes line-by-line.

Needless to say, that is very tedious — so much so that I, as a reasonably skilled Git user, get quite frequently enraged when I have to perform all of these changes, all manually.

I remember once when I had a PR where the CI failed due to the files not being

formatted up to par with Nixpkgs’s official formatter, and I had realized that I

had three commits, and all of them had formatting issues of some sort. I had to

first individually format them, then add each file to its own commit, then using

git rebase -i to reorder these commits after the ones they are supposed to

change, changing them to fixup, and then wait for rebasing to slowly amend

those existing commits.

$ nvim # Work work work

$ git add pkgs/by-name/fo/foo/package.nix

$ git commit -m "foo fixes"

$ git add pkgs/by-name/ba/bar/package.nix

$ git commit -m "bar fixes"

$ git add pkgs/by-name/qu/quux/package.nix

$ git commit -m "quux fixes"

$ git rebase -i HEAD~6

> pick 107839e foo: init at 0.1.0

> fixup 5a6b58d foo fixes

> pick 8d86303 bar: init at 0.4.20

> fixup 27967cc bar fixes

> pick f1bf11c quux: init at 11.4.514

> fixup 88efabc quux fixes

... after a while ...

Successfully rebased and updated refs/heads/my-feature.

With Jujutsu, all I have to do:

$ jj fix

Fixed 3 commits of 3 checked.

Working copy now at: x[urmpxnpkzzu] 6[287ecba8978] (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : m[lxuqznxkqpl] 8[8efabc40682] quux: init at 11.4.514

Added 0 files, modified 3 files, removed 0 files

And Jujutsu would go through all of my commits, run the formatter for each file that each commit touches, amend the commits automatically, and rebase descendant commits for me, all in one command (provided that I have the formatter configured beforehand).

When I accidentally discovered a bug in one of my files, I can first find the

commit it belongs to with the jj log command, fork out a new commit after it,

make my changes, then squash it onto the existing commit, amending it, instead

of going through git rebase -i hell again.

$ jj log

@ x[urmpxnpkzzu] Leah Amelia Chen <[email protected]> 5 minutes ago 6[287ecba8978]

│ (empty) (no description set)

○ m[lxuqznxkqpl] Leah Amelia Chen <[email protected]> 5 minutes ago HEAD@git 8[8efabc40682]

│ quux: init at 11.4.514

◆ u[vxnmqmttrpn] Leah Amelia Chen <[email protected]> 3 weeks ago main main@origin 2[7967cce5625]

│ bar: init at 0.4.20

~

$ jj new u

Working copy now at: r[zlnvqxxvvxt] e[49620f51495] (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : u[vxnmqmttrpn] 8[8efabc40682] bar: init at 0.4.20

$ nvim # Work work work

$ jj squash

Working copy now at: q[uwpwkulnpwl] 3[b8d10f9daed] (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : u[vxnmqmttrpn] 1[21307eae7aa] bar: init at 0.4.20

It’s also worth nothing that, in the jj new call, I did not use the full name

of the commit (known as the Change-ID, or the keyboard spam I described earlier)

— I typed u, instead of uvxnmqmttrpn. This is because by default Jujutsu

shows you the unique prefix of the commit in color, and the rest of the commit

is grayed out (shown in brackets for this article since I am too lazy to set up

the right colors in codeblocks).

You don’t have to guess how many digits of the commit SHA you need to specify, unlike Git, since you can just see it for yourself.

The Change-ID also doesn’t change after rebases or amends, which means that you

don’t really even have to look at jj log that often — a command that had

already targeted a commit will continue to work.

You can even easily split a commit in half with jj split, which, when given no

paths are selected, produces a delightful, builtin TUI that allows you to select

changes file-by-file, line-by-line, instead of interacting with the likes of

git add -p, which is about as intuitive as unironically using ed to edit

files. The same TUI is also used for conflict resolution, and now I finally

don’t have to go insane trying to resolve changes in Neovim while every single

line is underscored with red squiggly lines.

Along with other goodies like built-in expressions for selecting revisions and files, customizable output, customizable tree view, etc., these really tiny, ergonomic touches truly makes Jujutsu a delightful tool to interact with, at least for the extremely squash-friendly, make-every-commit-airtight-and-crystal-clean approach Nixpkgs takes. Instead of stage-commit-push-amend-rebase-forcepush, it’s just commit-push-new-squash-push. It works wherever you are, no matter your worktree looks like, regardless of what commit you’re working on.

(Oh, did I say that Jujutsu force pushes by default? Thank god I don’t have to

manually specify --force-with-lease every single damn time I have to push my

changes now…)

And no matter what you do, if you screw up, there’s always jj undo.

I now do not understand how I survived 5 years of using Git without an undo button.

Despite the fact that it’s been overall a very useful addition to my workflow, and dare I say it, it singlehandedly made me feel much less tired of doing open-source work, as it lifted the cognitive burden and physical tedium Git provides that makes me feel like I’m hitting a brick wall every time I want to fix my commits, I have to admit that Jujutsu is not perfect — nothing is, really.

Chapter III. Determining the Ultimate Verdict

Despite its many, many advantages I’ve outlined above, Jujutsu is admittedly

still a beta/experimental project — while it probably won’t corrupt your files

(unless you happen to Ctrl-C at really unopportune times, which is a habit from

Git that I really should get rid of and instead should just wait for it to

finish and run jj undo), there are still quite a few rough edges, mostly with

Git integration.

I’ve noticed that jj git fetch feels considerably slower than git fetch.

Granted, it does have to also convert the new Git commits into Jujutsu’s native

commits, but then I can’t shake the feeling that the physical download is also

much bigger — maybe I’ve just been blissfully unaware of just how big Git

updates can be, but I do think that maybe it’s fetching a lot more than what it

should.

Similarly for jj git push, which takes at least twice as long as a regular

git push --force-with-lease. This might be because it has to push

Jujutsu-specific data onto the upstream in addition to the Git commits, which is

especially exacerbated on a gigantic repository like Nixpkgs, with over 710’000

commits as of time of writing, and weighing nearly 6 gigabytes in my local copy

— but the point remains that perhaps there needs to be more investigation into

improving Jujutsu’s efficiency on larger repos. (This speed difference is

basically imperceptible on smaller repos, which suggests that this specifically

has to do with the size/commit count of the repository.

One of the agonizing sacrifices I’ve had to make in order to switch to jj is

gh pr create. The GitHub CLI really does not like it when the local

repository is in what it sees as a “detached HEAD” state (since it was managed

by Jujutsu), and I’ve tried to first let Jujutsu push a remote branch and then

letting the GitHub CLI pick it up. (It did not work.) In the end, I had to

settle for creating PRs with the web interface, which is considerably less

convenient for me as I used to be able to edit PR messages within Neovim at a

much faster speed, but considering how much more time I gain by using Jujutsu, I

deem the tradeoff worth it.

Finally, I would argue that the main reason why I view Jujutsu so positively is that it perfectly caters to my workflow in projects I usually contribute to. I’ve preached to many friends about how amazing Jujutsu has been for me, but some of them simply do not get the appeal as they mostly work alone on a solely push, no amend/squash workflow that lets the commit stack pile up at will.

And frankly, I get it. How useful is the ability to amend and squash changes into a commit if you don’t even really edit commits after they’re made, when nobody would be inspecting every nook and cranny of your commits and demand microscopic fixes for each of them? What I just described is my reality, and it did not line up with theirs, and it might not line up with yours.

Epilogue. Concluding the Superfluous Tirade

If you find the features I’ve praised here any bit interesting, you should give Jujutsu a try.

If you work with a squash-oriented pristine-commit workflow like I am, you should really give Jujutsu a try.

But beware that you may leave without finding much appeal to the tool, and not understanding what is the hype behind it: and that is totally okay.

Maybe you’d find my comparisons between Git and Jujutsu stupid, because I’m evidently “not good enough” at using Git, and don’t know about the black magic aliases and scripts people have come up with. My point is that these are fundamental ergonomic flaws of Git, which Jujutsu addresses with no hacking required.

You might find it acceptable to spend 15 actual minutes to split up a big commit

into seven, each individually labelled and inspected to conform to coding and

scope standards, with manual calls to git add -p and git commit, meanwhile I

can perform the same task in under five minutes with jj split, even when

learning how to use the TUI from scratch.

You might be satisfied with LazyGit. That’s fine too! But I find it seriously cool that you don’t need any tool other than Jujutsu to enjoy all of its advanced features. In fact, I think the fact that many people need a dedicated TUI tool on top of Git just to make sense of it, speaks volumes about how unintuitive Git itself is.

In spite of all of these concerns and objections, I would still recommend Jujutsu. After all, how could you know if something works for you, if you don’t try and feel how well it works yourself?